Program Notes for Pastiche

Fauré, Messe basse, composed 1881, for voices (SSA) and organ

Fauré, Messe basse, composed 1881, for voices (SSA) and organ

Adaptation for four voices and chamber orchestra by Jon Washburn

A GENTLE MASS

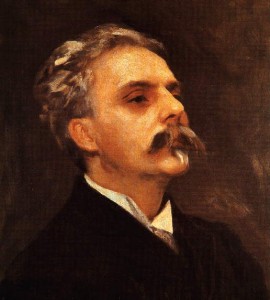

The Missa brevis is a shortened version of the Mass in which the Mass is either performed with complete text, but with simple, often syllabic,settings, or in which part of the Mass is either omitted or spoken rather than sung. In some cases it belongs to a genre of shortened weekday masses (in contrast to the more elaborate Sunday forms) in which the Gloria and Credo are either omitted or simply spoken. Different Christian traditions have unique versions of this essential pattern of usage. The French messe basse is simply a Low Mass which can either be totally spoken to the accompaniment of music or in which only certain parts are sung. Fauré’s Messe basse is a prime example. Fauré detested the bombastic 19th-century settings of the Mass, particularly that of Berlioz, whose grandiose spectacle emphasized the wrath and judgments of God, whereas Fauré felt that the mass should be all about mercy and forgiveness. The Messe Basse reflects this attitude in its gentle voicing and scoring, anticipating the same effect more fully Gabriel Fauré achieved in his more famous Requiem.

According to liner notes by Jeremy Cull for a Lammas recording, 2001, “The Messe Basse dates from about 1880, although not published until 1907, and is scored for treble voices and organ. Fauré omits the Gloria and Credo – sections of the Mass that give most scope for dramatic writing – concentrating instead on the Kyrie, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei, imbuing them with a quiet lyricism that is also to be found in his songs and some of his quieter piano works; in this respect, the writing in the Messe Basse anticipates his approach to the Requiem. In the Kyrie and Benedictus Fauré sets a solo voice against the rest of the choir, whilst in the other two movements, the treble voices are divided equally in two.”

Franz Joseph Haydn – Concerto in C Major, Hob. VIIb1

Franz Joseph Haydn – Concerto in C Major, Hob. VIIb1

THE GENIUS OF CLASSICISM

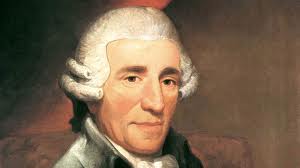

“After you’ve listened to everyone else, its good to hear a little Mozart to clean out your ears.” So goes the old saw, and anyone who knows music is likely to agree. Whatever it was that guided Mozart’s genius (and that so maddened men of lesser talent, like Salieri) there is something unique and wonderful about his music — his unfailing sense of proportion, absolute perfection in combining beautiful sound with elegant rhetoric, and the uncanny ability to turn potentially bland and ordinary ideas into moments of sheer enchantment and even spiritual ecstasy.

But there is another side to classicism that cannot and should not be ignored, requiring a different kind of genius, a genius that speaks less the refined language of Viennese splendor than the direct, some might say simple or rustic, vernacular of Eisenstadt and Esterhazy — the kind of down-to-earth eloquence we have come to associate with Lincoln and which found its fullest musical expression in Beethoven.

Mozart could reel off five or six splendid ideas, one after another, all of them highly integrated and harmonious, with hardly a thought. Haydn, by contrast, was more economical but no less imaginative. His seemingly limitless melodic invention (at least 109 symphonies, for example), coupled with boundless energy, always manages to suggest a certain directness, simplicity, naïveté — however it

is characterized — that reflects something of a constructionist mentality compared to Mozart’s lavish spontaneity.

SOPHISTICATION AND COUNTRY CHARM

SOPHISTICATION AND COUNTRY CHARM

Both men — Mozart and Haydn — spoke with integrity, Haydn’s music reflecting his peasant origins and the hardscrabble existence of his childhood and youth, while Mozart’s urbane dialect suggests a very cerebral world dominated early on by the sophistication of court and church. That each man, in his own way, was able to transcend what could have been serious existential limitations, is a testament to the character and quality of their individual gifts and powers.

Clearly, the elegant genius of Mozart is in no way lessened by giving Haydn his due. It is fair to say that Haydn adds a dimension to 18th-century music that is, shall we say, less evident in Mozart. Thus, if your taste runs a little less to suave refinement and rounded edges, and a little more toward charm, Haydn might very well be your man. That he managed to write music with immediate appeal Franz Joseph Haydn without sacrificing subtlety and nuance turns out to be one of the most endearing qualities of his music.

THE C LASSICAL CONCERTO

LASSICAL CONCERTO

For those who love orchestral music, it doesn’t get much better than a good Classical concerto. And there is nothing quite like the deep resonant bass and rich, soaring, middle-range melody of the cello. Tonight, we are fortunate to hear the first of Haydn’s two cello concertos, the Concerto in C Major, Hob. VIIb1, a work which fulfills all the important criteria of a classical concerto, performed by a master. Spurred by a 1962 performance by Milos Sádlo and the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra, the concerto has enjoyed a renaissance in the last fifty years and has once again become a staple in the cello repertory.

An early work, it is cast in three movements (moderato, adagio, allegro molto) and still retains elements of the baroque ritornello structure in which tutti and solo passages alternate freely. But each of the three movements also clearly manifests the sonata principle in that the major divisions of the opening section (exposition) are harmonically defined by a primary (tonic) key and a secondary (dominant) key, followed by a brief period of free harmonic and thematic exploration (development) and a return (recapitulation) to the opening musical material in the original key, to form a rounded formal architecture (statement, departure, restatement).

Typical of the times, the orchestra for this concerto is made up of the tutti (full instrumental complex, including strings, two oboes and two horns), the solo (in this case a cello), and the continuo (a harpsichord, to provide the undergirding harmonic foundation, and a cello or string bass to reinforce the bass line). Undoubtedly reflecting the outstanding skill of the lone cellist in the Esterházy orchestra, the solo part is highly virtuosic, a reminder that the quality of performance in the best 18th-century orchestras paralleled the state of near perfection which had been attained in stringed instruments themselves in the previous (17th) century. Another typical element of each movement is the cadenza, an improvised virtuosic reinterpretation of the thematic material by the soloist, leading in virtually all concertos of this period to the final tutti or ritornello.

Typical of the times, the orchestra for this concerto is made up of the tutti (full instrumental complex, including strings, two oboes and two horns), the solo (in this case a cello), and the continuo (a harpsichord, to provide the undergirding harmonic foundation, and a cello or string bass to reinforce the bass line). Undoubtedly reflecting the outstanding skill of the lone cellist in the Esterházy orchestra, the solo part is highly virtuosic, a reminder that the quality of performance in the best 18th-century orchestras paralleled the state of near perfection which had been attained in stringed instruments themselves in the previous (17th) century. Another typical element of each movement is the cadenza, an improvised virtuosic reinterpretation of the thematic material by the soloist, leading in virtually all concertos of this period to the final tutti or ritornello.

Among the many interesting things to listen for:

- full 4-string chords in the cello;

- exploitation of the cello’s very high register, as if it were a violin;

- rapid changes in register, high and low, suggesting that the soloist is playing his own counterpoint

Most of all, however, the listener should engage the sheer joy and energy of the sound and become, insofar as it is possible, one with the soloist and the orchestra, as Haydn invites us, two- and-a-half centuries after its creation, into his own private world of sensation and perception.

Morten Lauridsen, Les Chansons des roses

(1993) on texts from Les Roses, published 1927,

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926)

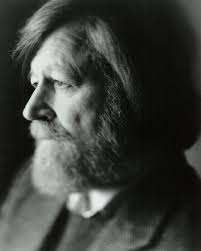

Morten Lauridsen (b. 1943) is one of the most successful living choral composers in the world, today. Educated at Whitman College and the University of Southern California, he joined the U.S.C. faculty in 1967, where he founded the renowned U.S.C. program for scoring film and television music. Winner of numerous awards, in 1994 he became composer-in-residence for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, for whom he composed the motet O Magnum Mysterium, one of the most Roses in a bottle 1904 -Cezanne frequently recorded and performed choral works Morten Lauridsen in history. Tonally conservative in style, his music has broad appeal and seems to reflect the surrounding of his favorite composing place, a small, tranquil island off the coast of Washington state.

Morten Lauridsen (b. 1943) is one of the most successful living choral composers in the world, today. Educated at Whitman College and the University of Southern California, he joined the U.S.C. faculty in 1967, where he founded the renowned U.S.C. program for scoring film and television music. Winner of numerous awards, in 1994 he became composer-in-residence for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, for whom he composed the motet O Magnum Mysterium, one of the most Roses in a bottle 1904 -Cezanne frequently recorded and performed choral works Morten Lauridsen in history. Tonally conservative in style, his music has broad appeal and seems to reflect the surrounding of his favorite composing place, a small, tranquil island off the coast of Washington state.

Lauridsen has enjoyed great success with the type of choral cycle represented in tonight’s program, Les Chansons des Roses, on texts by the renowned Austrian-Bohemian novelist and poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Given Lauridsen’s love of nature and his profoundly spiritual temperament, it is easy to grasp his attraction to Rilke, who is widely regarded as one of the strongest poetic voices in the search for ineffable meaning in a secular age. Through a marriage to a former student of the poet Rodin, Rilke became Rodin’s secretary for a number of years, while living in Paris — the city which became the center of his poetic activity. There he became attracted to modernism and was influenced by the work of Cezanne.

Lauridsen has enjoyed great success with the type of choral cycle represented in tonight’s program, Les Chansons des Roses, on texts by the renowned Austrian-Bohemian novelist and poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Given Lauridsen’s love of nature and his profoundly spiritual temperament, it is easy to grasp his attraction to Rilke, who is widely regarded as one of the strongest poetic voices in the search for ineffable meaning in a secular age. Through a marriage to a former student of the poet Rodin, Rilke became Rodin’s secretary for a number of years, while living in Paris — the city which became the center of his poetic activity. There he became attracted to modernism and was influenced by the work of Cezanne.

But it was Rodin’s influence that really formed his poetic vision. Rodin taught him

to observe objects as things in themselves, and from that new power of observation he shaped a poetic language which focused on objective form.

Rainer Rilke

Rainer Rilke

The rose appears frequently as an image in Rilke’s poetry and served as the subject for his collection Les Roses, from which Lauridsen drew the five poems in his Les Chansons des Roses. It appears that the rose represented for him the ultimate contradictions of love — the perfection of beauty countered inevitably by its thorns.