‘Tis the Season: Program Notes

Program Notes

— Dr. Roger Miller, Professor Emeritus, University of Utah.

A Ceremony of Carols

A Ceremony of Carols

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

INSPIRATIONAL MUSIC BLOSSOMS AMID UNINSPIRING SURROUNDINGS

British composer Benjamin Britten was in America when WWII began. Rather than remain safe in the USA, Britten, a pacifist, chose to express his national pride and loyalty by returning to his native land to bear the trials and hardships of the war with his own people.

Crossing the Atlantic by ship was a dangerous undertaking in May,1942, because of the ever-present Nazi U-boats. Passage was booked on one of the few ships available: a Swedish (ostensibly neutral and, therefore, presumably safe) cargo vessel. According to Peter Pears, Britten’s friend and traveling companion, accommodations on board the MS Axel Johnson were remarkably unaccommodating: noisy, smelly, and claustrophobic.

A port-of-call visit to a bookstore in Halifax, Nova Scotia, had put into Britten’s hands just the thing to assuage the tedium (and worry?) of the voyage: a copy of The English Galaxy of Shorter Poems. To relieve the tension Britten spent much of his time composing music. Two exceptionally fine choral pieces were completed during the crossing: the Hymn to St. Cecilia (on a text by W. H. Auden), and A Ceremony of Carols, inspired by the poetry discovered in his Halifax purchase.

A port-of-call visit to a bookstore in Halifax, Nova Scotia, had put into Britten’s hands just the thing to assuage the tedium (and worry?) of the voyage: a copy of The English Galaxy of Shorter Poems. To relieve the tension Britten spent much of his time composing music. Two exceptionally fine choral pieces were completed during the crossing: the Hymn to St. Cecilia (on a text by W. H. Auden), and A Ceremony of Carols, inspired by the poetry discovered in his Halifax purchase.

First conceived as individual carols for three-part treble voices and harp, the concept changed to that of a cycle framed by a processional and recessional. But the transition was somewhat complicated. During the crossing itself, Britten composed seven carols, only five of which were eventually included as written (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 8, and 10). Another of the original seven was a setting of the Latin text “Hodie Christus natus est” (“Today, Christ is born”). Upon returning home, Britten decided to substitute a Gregorian antiphon (also a setting of the “Hodie” text) for his processional and recessional, and transfer his setting made at sea to the now very popular “Wolcum Yole!” (No. 2 in the set). Subsequently, three additional pieces were added. Lacking an appropriate traditional title, Britten chose to call his extraordinary cycle, simply, a “ceremony” of carols. Now an iconic musical landmark, A Ceremony of Carols (subsequently arranged for SATB voices), is performed around the world at Christmas time.

First conceived as individual carols for three-part treble voices and harp, the concept changed to that of a cycle framed by a processional and recessional. But the transition was somewhat complicated. During the crossing itself, Britten composed seven carols, only five of which were eventually included as written (Nos. 3, 5, 6, 8, and 10). Another of the original seven was a setting of the Latin text “Hodie Christus natus est” (“Today, Christ is born”). Upon returning home, Britten decided to substitute a Gregorian antiphon (also a setting of the “Hodie” text) for his processional and recessional, and transfer his setting made at sea to the now very popular “Wolcum Yole!” (No. 2 in the set). Subsequently, three additional pieces were added. Lacking an appropriate traditional title, Britten chose to call his extraordinary cycle, simply, a “ceremony” of carols. Now an iconic musical landmark, A Ceremony of Carols (subsequently arranged for SATB voices), is performed around the world at Christmas time.

Not all of the poems refer to Christmas as we think of it, on the 25th of December. For example, Nos. 5 (“As dew in Aprille”) and 9 (“Spring Carol”) reflect the popular belief that the Christ child was actually born in the early spring, his birth coinciding with the traditional birthing time of lambs in the Holy Land. Other poems clearly allude to winter festivities and temperatures (“Wolcum Yole!” and “In Freezing Winter Night”).

ILLUMINATING THE TEXT

No. 1 Processional, “Hodie Christus natus est . . . Gloria in excelsis Deo.”

No. 2 (“Wolcum Yole”), a joyous introduction to all the festivities surrounding Christmas, including Christmas Day, New Year (which, before the Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1582, occurred in March, coinciding with the arrival of Spring), Twelfth Day, and “Candelmesse.” Thus, the text works well for either interpretation of the date of Christ’s birth, Winter or Spring.

No. 3, “There is no Rose,” makes reference to a venerated Christmas myth based on a passage in Isaiah (11:1ff.), thought by Christians to refer to the Messiah: “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots.” The notion grew in Europe that the Biblical metaphor referred to the Virgin Mary as the source of eternal life, through her giving birth to Jesus, as exemplified by a flowering evergreen plant (genus Helleborus) popularly known as a “Christmas rose,” which remained green throughout the winter. Although the plant in question (ranunculus or buttercup) was not a member of the rose family, the idea of representing Christ’s mother as a rose ‘took root’, as it were, and is a common theme in medieval literature.

No. 3, “There is no Rose,” makes reference to a venerated Christmas myth based on a passage in Isaiah (11:1ff.), thought by Christians to refer to the Messiah: “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots.” The notion grew in Europe that the Biblical metaphor referred to the Virgin Mary as the source of eternal life, through her giving birth to Jesus, as exemplified by a flowering evergreen plant (genus Helleborus) popularly known as a “Christmas rose,” which remained green throughout the winter. Although the plant in question (ranunculus or buttercup) was not a member of the rose family, the idea of representing Christ’s mother as a rose ‘took root’, as it were, and is a common theme in medieval literature.

No. 4, in two sections, is Mary’s comforting “The Yonge Child” when he begins to cry, followed by a nightingale’s song, and “Balulalow,” a simple cradle song or lullaby.

No. 5 (“As dew in Aprille”), an anonymous hymn to the Virgin,the young maiden who became the Mother of God. Especially touching is the poetic refrain, “He came all so still,” which guides us through three different aspects of the Holy Birth and concludes with the lovely thought:

Moder and mayden was never none but she:

Well might such a lady Goddes moder be.

No. 6 (“This little Babe”) is a rousing sequel to the reflective poems preceding it. Here we see the wonderful metamorphosis taking place in Jesus’ life: Now, only a helpless babe, He is in fact the Master of the Universe, come to destroy or “rifle Satan’s fold.” Rife [!] with military symbolism, the poem portrays Christ as the great general leading us, his soldiers, into the cosmic fray, while the music contributes a driven, portentous accompaniment. In this piece, and in the finale, “Deo Gracias,” there are harp-like effects and a stretto featuring a wonderfully conceived canon.

No. 7 Interlude (harp solo)

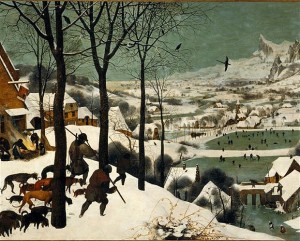

No. 8 (“In freezing winter”). The image is that of the Euro-centric Middle Ages: Christmas as a winter holiday and Jesus as a hapless peasant boy, born in the same rude circumstances in which peasants have always lived. Freezing, bare and cold, the stable is portrayed as a bleak, unlikely place for the birth of the Son of God. Nevertheless, His very presence makes of the manger a Prince’s court. A more recent theory suggests that the shepherds of Bethlehem were in fact priests caring for the special flocks from which came the unblemished lambs being prepared for Temple sacrifice. It lends credibility to the notion of an early spring birth, when such lambs would have been born. The stable, in this more noble view, was not a dirty animal shelter, but a place of scrupulous ritual cleanliness where the young lambs would have been carefully swaddled in warm cloth, just like the newborn Jesus, Himself the unspotted Lamb of God who would, like them, give His life in innocent expiation for the sins of the world. But the image of “God with us,” born in a lowly stable surrounded by sympathetic beasts, even as He was rejected by a thoughtless, uncaring world, persists as one of the enduring and endearing myths of Christmas and is here portrayed in all its naïve loveliness.

No. 8 (“In freezing winter”). The image is that of the Euro-centric Middle Ages: Christmas as a winter holiday and Jesus as a hapless peasant boy, born in the same rude circumstances in which peasants have always lived. Freezing, bare and cold, the stable is portrayed as a bleak, unlikely place for the birth of the Son of God. Nevertheless, His very presence makes of the manger a Prince’s court. A more recent theory suggests that the shepherds of Bethlehem were in fact priests caring for the special flocks from which came the unblemished lambs being prepared for Temple sacrifice. It lends credibility to the notion of an early spring birth, when such lambs would have been born. The stable, in this more noble view, was not a dirty animal shelter, but a place of scrupulous ritual cleanliness where the young lambs would have been carefully swaddled in warm cloth, just like the newborn Jesus, Himself the unspotted Lamb of God who would, like them, give His life in innocent expiation for the sins of the world. But the image of “God with us,” born in a lowly stable surrounded by sympathetic beasts, even as He was rejected by a thoughtless, uncaring world, persists as one of the enduring and endearing myths of Christmas and is here portrayed in all its naïve loveliness.

No. 9 (“Spring Carol”), again a reference to the probable season in which Christ was born. Though we often think of carols as relating specifically to Christmas, the term “carol” denotes only a type of folk song, suggesting carefree joy and happiness. This carol is a duet of thanksgiving, filled with images of Spring; it sings of “deer in the dale, sheep in the vale, and corn (grain) springing out of the ground.”

No. 10 (“Deo gracias” or “Thanks be to God.”) sometimes titled “Adam lay ibunden.” Here, the “ceremony” takes a theological turn, referring to fall of man and the great atonement, the ultimate purpose for which Christ became man: to save us from the bonds of death and hell occasioned by the sin of Adam (here symbolized by an “apple”) in the Garden of Eden. With its dynamic introduction and repetition of the phrase, “Adam lay ibunden,” this is one of the most vivid of the carols and a fitting climax to the cycle.

No. 11, Recessional, a reprise of the Gregorian antiphon, “Hodie, Christus natus est.”

No. 11, Recessional, a reprise of the Gregorian antiphon, “Hodie, Christus natus est.”

Twenty Polish Christmas Carols

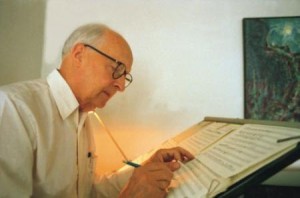

Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994)

THE ADORATION OF MARY

Several of the carols in this collection reference the Virgin Mary. The Veneration of Mary has deep roots in the folk traditions of many European countries, including Lutoslawski’s native Poland, a nation intimately connected with Roman Catholicism, and thus his religious as well as cultural homeland. Lutoslawski clearly found such texts as “Holy Lady Mary,” compatible with his own sensibilities; yet we find nothing in them to suggest religious dogma. Instead, they reflect the simple virtues of a weary young mother seeking a place of rest for the imminent birth and care of her first child. As such, they relate to a universal tradition of empathy and admiration for the calling of motherhood, and form an integral part of the Christmas narrative. Other carols likewise focus on traditional aspects of the nativity story: the star, angels and shepherds, Bethlehem, the manger, the tiny infant, etc., with only occasional hints of the theological implications surrounding Jesus’ divinity, all captured in these charming but far from hackneyed settings. Accustomed as we are to the trite and the “commercial” in so much of the music of Christmas, these fresh, artfully composed pieces are a welcome addition to the season’s repertoire.

Several of the carols in this collection reference the Virgin Mary. The Veneration of Mary has deep roots in the folk traditions of many European countries, including Lutoslawski’s native Poland, a nation intimately connected with Roman Catholicism, and thus his religious as well as cultural homeland. Lutoslawski clearly found such texts as “Holy Lady Mary,” compatible with his own sensibilities; yet we find nothing in them to suggest religious dogma. Instead, they reflect the simple virtues of a weary young mother seeking a place of rest for the imminent birth and care of her first child. As such, they relate to a universal tradition of empathy and admiration for the calling of motherhood, and form an integral part of the Christmas narrative. Other carols likewise focus on traditional aspects of the nativity story: the star, angels and shepherds, Bethlehem, the manger, the tiny infant, etc., with only occasional hints of the theological implications surrounding Jesus’ divinity, all captured in these charming but far from hackneyed settings. Accustomed as we are to the trite and the “commercial” in so much of the music of Christmas, these fresh, artfully composed pieces are a welcome addition to the season’s repertoire.

Charles Bodman Rae made the English translations used in tonight’s performance. An edited version of his translator’s notes is reproduced here for the wealth of interesting and informative insights they provide.

As far as is known, Christmas songs were first introduced to Poland by Franciscan monks in the thirteenth century. These examples of nativity celebration were Latin church songs rather than the more secular folk song tradition which we tend to associate with carols; but even from this early stage, the Franciscans cultivated stories which emphasized the manger as the focal point for identifying with the humble birth of Christ. The earliest surviving sources of the Latin texts date from the fifteenth century; but they do not contain the melodies, which were passed down through an aural rather than written tradition.

As far as is known, Christmas songs were first introduced to Poland by Franciscan monks in the thirteenth century. These examples of nativity celebration were Latin church songs rather than the more secular folk song tradition which we tend to associate with carols; but even from this early stage, the Franciscans cultivated stories which emphasized the manger as the focal point for identifying with the humble birth of Christ. The earliest surviving sources of the Latin texts date from the fifteenth century; but they do not contain the melodies, which were passed down through an aural rather than written tradition.

By the sixteenth century, widespread popularity of Christmas songs had led to increasing secularization, with texts in the vernacular, improvised instrumental accompaniments, and tunes that owed more to folk music than the Church. The addition of archetypal shepherd characters to the stories, with Slavonic rather than biblical names (e.g. Bartos and Kuba) led to a great increase in their popularity, due to the degree of identification with familiar [i.e. Polish] pastoral images.

RE-INVENTING THE CAROLS

For his set of 20 carols, Lutoslawski took traditional texts and melodies from several collections gathered during the mid-nineteenth century. His settings for voice and piano (1946), made in response to a commission from the Polish Music Publishers, treat the traditional diatonic melodies with accompaniments that complement rather than correspond to their harmonic implications. A pervading harmonic principle is the skillful interchange of chromatically moving major and minor thirds, which modifies the diatonic functions of the tunes without entirely undermining them. One can also observe Lutoslawski’s characteristic technique of combining two types of interval in order to generate a melodic line. Throughout the whole set of carols, the accompaniments display a high degree of ingenuity and invention which places them more on the level of miniature compositional studies than mere arrangements, revealing a sophistication of harmony behind their apparent simplicity.

For his set of 20 carols, Lutoslawski took traditional texts and melodies from several collections gathered during the mid-nineteenth century. His settings for voice and piano (1946), made in response to a commission from the Polish Music Publishers, treat the traditional diatonic melodies with accompaniments that complement rather than correspond to their harmonic implications. A pervading harmonic principle is the skillful interchange of chromatically moving major and minor thirds, which modifies the diatonic functions of the tunes without entirely undermining them. One can also observe Lutoslawski’s characteristic technique of combining two types of interval in order to generate a melodic line. Throughout the whole set of carols, the accompaniments display a high degree of ingenuity and invention which places them more on the level of miniature compositional studies than mere arrangements, revealing a sophistication of harmony behind their apparent simplicity.

In 1985 Lutoslawski orchestrated 17 of the carols for a performance with the London Sinfonietta and Chorus. The remaining three carols, however, were not orchestrated until some four years later for a performance with the Scottish Chamber Chorus and Orchestra in 1990.

In 1985 Lutoslawski orchestrated 17 of the carols for a performance with the London Sinfonietta and Chorus. The remaining three carols, however, were not orchestrated until some four years later for a performance with the Scottish Chamber Chorus and Orchestra in 1990.

Tonight’s performance features the carols arranged in the order established by the composer for the 1990 performance. The juxtaposition of these Lutoslawski carols with Britten’s Ceremony of Carols makes for an exciting contrast of styles, techniques, and means. Combining one of the most profound events of human history with artistic sensitivity and the childlike naiveté that is so much a part of it, each work has the potential to carry the listener into realms of marvelous beauty and personal reflection. But the realization of great art is always a communication between creator, performer, and listener. Only a group such as the Utah Chamber Artists has the wide range of flexibility and skill to do justice to these vivid portrayals of the images and emotions of Christmas. We hope that you, our audience, will join them in making this evening a musical highlight of your Holiday Season.