Program Notes: Collage 2016

“Journeys of the Heart”

Utah Chamber Artists Collage Concert

Monday September 26, 2016

by Roger Miller, Professor Emeritus, University of Utah

JOURNEY THROUGH SPACE & TIME – an introduction

For a previous UCA concert, Becky Durham wrote a note that is an appropriate introduction for tonight’s program, “Journeys of the Heart.”

In 1935 composer Herbert Howells lost his nine-year-old son Michael to meningitis. To make his way through his grief he turned, not surprisingly, to music. In his own words: “The sudden loss of an only son, a loss essentially profound and, in its very nature, beyond argument, might naturally impel a composer, after a time, to seek release and consolation in language and terms most personal to him. Music may well have the power beyond any other medium to offer that release and comfort.”

While tonight’s subject is not limited to music of consolation, it does follow a theme that requires understanding and empathy.

One definition of the word “melancholy” is “thoughtful sadness,” or, one might say, a time of serious reflection on one’s state or place in life. Such reflection, from time to time, is not only inevitable but healthy, if by doing so we gain perspective and are thus able to continue the journey of life with confidence, joy, and a deep respect for one another as we face the challenges of each day.

As tonight’s program unfolds, we journey through place and time in a way that allows a kind of universal glimpse into the heart journeys common to all of us as we make our way through the ups and down of life. We begin in England, where the poet William Blake articulates the hope that a “new Jerusalem” may rise from the ruinous defilement of nature caused by the industrial revolution. From there we are taken to an enchanted scene of moonlight (“Die Mainacht”) in which a nightingale’s song of fidelity and love only deepens a forgotten, rejected man’s inner world of loneliness and despair. Donald Skirvin’s Alchemy reminds us of a richly-nuanced line from Sara Teasdale:

“It is strange how often a heart must be broken

Before the years can make it wise.”

Without a precise poetic allusion, David Froom’s “Fast and Furious” seems to epitomize the textures and pacing of our modern world. It is followed by the soothing naïveté of Daniel Elder’s “Lullaby.” Louis Vierne’s “Hymne au soleil” (Hymn to the Sun, probably 4 inspired by Lamartine’s poem of that title) speaks of the sun as a metaphor of the Eternal, a recurring source of optimism and beauty on a path too often marred by pain and disbelief.

Brahms’ soaring Alto Rhapsody takes us to the wilderness of scorned desire. The wanderer, lost in his desert of hubris and self-pity, turns at last to the Father of Love and His Psalter, begging for one note to quench the misanthropic burning of his tortured heart. As if to assuage this bitter thirst, Herbert Howells’ setting of the Magnificat rejoices in Mary’s humility before the Source of all comfort and hope: “My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Savior.” Eugene Ysaÿe’s “Malinconia” (Melancholy) briefly returns to the theme of “thoughtful sadness” as the singers, orchestra and dancers perform J.A.C. Redford’s Rest Now, My Sister, a profound meditation in the face of tragic death.

Quickly changing the mood — or perhaps in response to it, Louis Vierne’s “Feux follets” (Will-o’-the-wisp) presents a phantasmagoria (“a rapidly shifting scene of real or imagined figures”) in this scherzo-like selection from the 24 Pièces de fantasie. Two songs from Brahms’ Neue Liebeslieder warn of the perils of love. The first, “Nein, Geliebter, setze dich,” hopes to keep secret a budding romance. Far from coy shyness, the second, “Flammenauge, dunkles Haar,” speaks passionately of “flaming eyes and dark hair.” In the same vein, the “Segudilla” from Bizet’s Carmen is sung by a hot-blooded gypsy girl who uses her wiles to escape from a Spanish jail, but in doing so destroys both the guard who succumbs to her and, by his betrayal, his virtuous and innocent sweetheart.

Thus, for better or for worse, the many journeys of the heart come to a close, but not without closure. The finale provides our musical narrative with transcendent fulfillment. The traveler is found, as it were, among the Children of Israel at Mt. Sinai. Moses, holding the word of God on tablets of stone, descends from the mountain, aglow with holy fire. Drawing his text from Psalm 47, composer Ralph Vaughan Williams sounds the ram’s horn, calling the congregation together: “O clap your hands, all ye people. Shout unto God with the voice of triumph. For the Lord most high is terrible; he is a great king over all the earth. Sing ye praises unto our King.”

Music to be performed:

1. Jerusalem

1. Jerusalem

Hubert Parry (1848-1918), text by William Blake

Hubert Parry’s setting of the William Blake poem “Jerusalem” has been called an “anthem for England.” But, now known and loved around the world, “Jerusalem” has long since transcended its specifically British ties. Blake’s poem is based on a hallowed but apocryphal tradition that the young Jesus was brought to England’s shores by Joseph of 5 Arimathea, the same who would later provide a burial tomb for the crucified Christ. The thought that Jesus might have walked upon England’s “green and pleasant land” has been a source of pride for generations of Englishmen and is closely connected with the Arthurian legends and the Knights of the Holy Grail. If the industrial revolution destroyed much of England’s natural beauty, along with the demise of her ancient traditions, Blake’s words articulate the hope that a “new Jerusalem” might someday rise to reclaim her glorious and sacred past.*

*Tradition holds that Joseph of Arimathea was a tin merchant, attracted by the famous mines of Cornwall (cf. the popular TV series, Poldark); he is also thought by some to have been the founder of the nearby Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset in the 1st century.)

2. Die Mainacht, Op. 43, No. 2

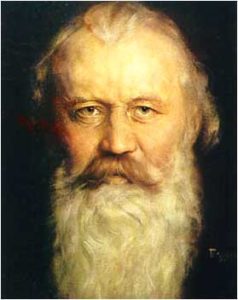

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

texts by Ludwig H. C. Hölty (1748-1776)

After completing his famous Requiem in 1868, Brahms turned much of his attention to composing Lieder, such as the four songs of Op. 43. The death of his mother, for whom the Requiem was composed, heightened his predisposition to melancholy and perhaps foreshadowed the intense emotional frustration of his later years. His setting of “Die Mainacht,” a lyric metaphor of romantic bliss expressed through a nightingale’s singing, is probably an early reflection (he was then 35) of his inner loneliness and longing for a happy marriage that never came. The song is in three sections, the second being a development, and the third, a modified restatement of the beginning. When the return occurs it is felt as resignation rather than the consummation portended in the poem’s metaphor. Although Brahms avoids overt tone-painting, a careful matching of text and music reveals a skillful artist’s brush in portraying the wrenching descent from ecstatic hopes into despondent shadows.

3. Alchemy, songs 1 and 3

Donald Skirvin, (b. 1946)

The widely performed Seattle composer Donald Skirvin is a leading voice in the contemporary choral scene. His Alchemy is a set of four pieces derived from poems by the turn-of-the-century romantic poet Sara Teasdale (1884-1933). Tonight’s performance, interpreted by dancers from the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, features the first and third pieces, “Living Gold” and “Jewelled Blaze” — vivid images drawn from Teasdale’s poems “Alchemy” and “Driftwood.” Skirvin himself has provided the following insights:

The widely performed Seattle composer Donald Skirvin is a leading voice in the contemporary choral scene. His Alchemy is a set of four pieces derived from poems by the turn-of-the-century romantic poet Sara Teasdale (1884-1933). Tonight’s performance, interpreted by dancers from the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, features the first and third pieces, “Living Gold” and “Jewelled Blaze” — vivid images drawn from Teasdale’s poems “Alchemy” and “Driftwood.” Skirvin himself has provided the following insights:

“Just as the ancient practice of alchemy endeavored to turn dross into gold, this setting of Sara Teasdale poems traces through its four movements a series of poetic and musical transformations along life’s journey: grief turns into gold; impermanence and the fear of loss are transformed by love; a sheen of iridescence is conveyed to us by our lovers; and initially, the ultimate transformation occurs when we pursue the path that beauty unfolds for us. Critic David Vernier, in Classics Today, described Alchemy as “rich in imagery wrought by imaginative use of [sometimes jazz-inspired] harmony and apt, sensitive text-setting. And it’s also just plain gorgeous music that speaks well for this composer’s facility with voices . . .”

4. “Fast and Furious” from Sonata for Solo Violin, 4th movement

David Froom (b. 1951)

David Froom will not be new to Utah audiences, having served briefly as a member of the University of Utah Music Department’s composition faculty in the 1980s. With prize-winning compositions, multiple recordings, regular performances by the Smithsonian Institution’s 21st Century Consort, and honors ranging from the Kennedy Center’s Friedheim Awards (first prize) to the Music Teachers National Association Distinguished Composer of the Year in 2006, Froom has enjoyed a distinguished international career. Since 1989, he has been a member of the faculty of St. Mary’s College in Maryland. The four movements of his Sonata for Solo Violin all have English titles. The final movement, “Fast and Furious,” is exactly that, but expressive and listenable in the bargain.

5. “Lullaby” from Three Nocturnes

Daniel Elder (b. 1986) is from Athens, GA has the rare gift of making elegant music from deceptively simple ideas. His sonorities are transparently luminous, as are his unpretentious but perfectly conceived piano accompaniments. And he is both author and composer. This is choral singing of sheer beauty!

6. “Hymn au soleil” from 24 Pièces de fantaisie: Deuxième Suite, Op. 53

6. “Hymn au soleil” from 24 Pièces de fantaisie: Deuxième Suite, Op. 53

Louis Vierne (1870-1937)

Born virtually blind but with an unusual gift for music, renowned French organist Louis Vierne was one of the celebrated masters of the French romantic school inspired by the “symphonic” organs of the famous French builder, Aristide Cavaillè-Coll. A student of Cesar Franck and Charles Marie Widor, he became organist at the Cathedral de Notre Dame, Paris, in 1900 and served there until his death in 1937 (which, in the best romantic tradition, occurred during a concert encore at the console of the famous organ). Himself a revered teacher, Vierne passed the French tradition to a host of famous students, including such organ luminaries as Marcel Dupré and Salt Lake’s own Alexander Schreiner.

During much of Vierne’s tenure, the historic Notre Dame organ* was in a sad state decline. It was, he said, “filled with dust and dead bats and swallows and is perishing from mildew and dry rot. A few days ago one of the biggest of the organ’s 5,246 pipes only just missed crashing down on a crowd of worshippers. This is all due to lack of money. Notre-Dame parish is the poorest in Paris.”

Vierne, personally, set about to raise funds for its repair, with concert tours in Europe and later in America, raising not only significant amounts of money but also building his own reputation as one of the finest organists in the world. His compositions include six Organ Symphonies and the 24 Fantasy Pieces (1926-27), of which the beloved Carillon de Westminster is among the world’s most recognized concert pieces. Tonight’s program features two lesser known pieces from the same collection: Hymne au soleil (Hymn to the Sun) and, later in the program, Feux follets (Will-o’-the-Wisp); the first, grand with antiphonal pyrotechnics between the manuals and pedals, the second, as would be expected, lightly-textured and fanciful.

*On 12 December 2012, after 10 months’ restoration work and silence, the great organ of Notre Dame de Paris – the largest in France, with five keyboards, 109 stops and nearly 8,000 pipes – opened the festivities for the cathedral’s 850th Anniversary.

7. Rhapsodie, op. 53,

7. Rhapsodie, op. 53,

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), for contralto solo, male chorus, orchestra.

One of Brahms’ loveliest creations, the Alto Rhapsodie was composed in 1869 as a wedding gift for Julie Schumann, daughter of Robert and Clara Schumann. Its beauty, however, belies a tender secret: Brahms, himself, had hoped to marry the young woman. The text, three stanzas from Goethe’s ode Harzreise im Winter, was written on a journey through the Harz Mountains. Brahms must have seen something of himself in Goethe’s portrait of a man suffering intense spiritual pain. According to Brahms’ biographer Malcolm MacDonald,

“The poem is a meditation on the different kinds of life God ordains for different temperaments; the central stanzas, set by Brahms, concentrate on the fate of the man weighed down by fruitless struggles against the iron bonds of misery. A young man, turned misanthropic by sorrow, seeks solitude in the wilderness. A depiction of the desolate winter landscape into which this figure has strayed is followed by an analysis of his mental anguish and a prayer for a melody that can ‘restore his heart’ and bring comfort to the thirsting soul.

[Brahms] was rightly proud of the Rhapsody’s compactness of expression [introductory recitative, aria, and final chorus], somber beauty, and discreetly apposite textual illustration. The opening recitative, dark-hued in its scoring and graphic in its sense of emotional oppression, derives much of its effect from the rootless wandering around the basic C minor tonality which so aptly depicts the misanthrope’s losing his way in the trackless wilderness.

The sense of internal drama is further projected in the following aria, whose sinuous cross-rhythms of 6/4 and 3/2 evoke mental confusion, and whose impassioned rhetorical stress on the word Menschenhass* is one of the most ‘operatic moments in all Brahms. . . . the broad, chorale-like melody of the final section [appears] in a warm C major. Shared between soloist and the male chorus, this heart-easing music brings, if not fulfillment, an emotional stability that the work has sought since its outset. Religious form and gesture here limn the outlines of an inner struggle; and the supplication to ‘restore his heart’ is three times fervently repeated, in the manner of an Amen.”

*Misanthropy: extreme bitterness, disappointment, envy or despair regarding one’s own fate as compared to the apparent happiness or good fortune of others.

8. Magnificat from The Office of the Holy Communion (St. Paul’s)

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

It might seem strange that Herbert Howells, the son of a lay organist in an English Baptist Church, and who in later years would be known as “an unorthodox Christian,” should have become one of the major musical voices of the Anglican Church in the 20th century. But so it was. Because of his talents, the young Herbert was taken under the wing of some of England’s greatest musicians, given a sound musical education and ultimately a place in the English musical pantheon, along with Hubert Parry and such giants as Ralph Vaughan Williams and Edward Elgar.

Strongly influenced by the Tudor church music of the 16th century (Tallis, Byrd, and others), Howells was thoroughly mentored and thus influenced by Ralph Vaughan Williams. His Magnificat was composed in 1945 during the last year of his appointment at Cambridge as a memorial to his son Michael, who had died earlier (see the Introduction above). The following note regarding the Choral Evensong at London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral sheds some light on the parenthetical insert in the title: This is the one Cathedral service which is led almost entirely by music, with the Choir singing preces and responses, the psalm for that evening, the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis of the Canticles and also an anthem.

9. “Malinconia” from Violin Sonata No. 2 in A minor, op. 27

9. “Malinconia” from Violin Sonata No. 2 in A minor, op. 27

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931) Belgian violinist Eugène Esaÿe’s six sonatas for solo violin were dedicated to one of his contemporaries. The First Sonata, in G minor, was dedicated to Joseph Szigeti, whose performance of Bach’s solo sonata in the same key so inspired Esaÿe that he decided to compose something in emulation of Bach’s magnificent work but with updated techniques and new sound colors. The resulting Sonata, No. 2 in A minor, was dedicated to the French virtuoso Jacques Thibaud. Those who know and love the violin, with its near-perfect acoustics and unparalleled expressivity, regard its solo repertory with sublime awe. Esaÿe’s “Malinconia” recalls a quotation from Frederick H. Martens’ book, Violin Mastery: Whoever undertakes to play such music “must be a violinist, a thinker, a poet, a human being, he must have known hope, love, passion and despair, he must have run the gamut of the emotions in order to express them all in his playing.”

10. Rest Now, My Sister

J.A.C. Redford (b. 1953)

This work was premiered by the Utah Chamber Artists five years ago. Becky Durham’s program note from that performance, with slight alterations, is excerpted here:

J.A.C. Redford, his wife Le Ann, and their family faced unimaginable tragedy last December [2010] when LeAnn’s sister, Kristine Gabel Allred was murdered. Redford looked to words, initially, as he says, to “deal with my own grief and console my wife.” His sonnet “Rest Now, My Sister,” subsequently married to music, was painfully true to the circumstances of her death, yet, by expressing the heartbreak verbally and musically he found the means to summon peace. Framed by quotations from the traditional Latin Mass for the Dead (set as a solo chant), varied forms of the tender refrain, “Rest now, my sister,” serve as a thrice- recurring ritornello, heading each of the sonnet’s three quatrains, while the final line of the couplet concludes with the word “rest.” Bird imagery infuses the poem with descriptive phrases, both terrifying and comforting, and a f inal reference to the resurrection: O let the phoenix sing. For birdsong now may weave its golden nest and heart unclenched at last may learn its rest. Redford found inspiration in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem, “Peace”: When will you ever, Peace, wild wood dove, shy wings shut, Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs? When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? And in a reverse nod to Dylan Thomas, h e prays that “my sister’s soul may indeed ‘go gentle into that good night’ after a death of such unimaginable violence.” “Rest Now, My Sister” is a solemn, courageous and loving tribute. As brother-in- law and composer, Redford offers Kristine — and others who hear his piece — an exquisite, genuine response to her death and to her life. Just as other composers and artists have turned to what they know best to assuage their feelings, J.A.C. has taken an act of destruction and answered it with an act of creation.

J.A.C. Redford, his wife Le Ann, and their family faced unimaginable tragedy last December [2010] when LeAnn’s sister, Kristine Gabel Allred was murdered. Redford looked to words, initially, as he says, to “deal with my own grief and console my wife.” His sonnet “Rest Now, My Sister,” subsequently married to music, was painfully true to the circumstances of her death, yet, by expressing the heartbreak verbally and musically he found the means to summon peace. Framed by quotations from the traditional Latin Mass for the Dead (set as a solo chant), varied forms of the tender refrain, “Rest now, my sister,” serve as a thrice- recurring ritornello, heading each of the sonnet’s three quatrains, while the final line of the couplet concludes with the word “rest.” Bird imagery infuses the poem with descriptive phrases, both terrifying and comforting, and a f inal reference to the resurrection: O let the phoenix sing. For birdsong now may weave its golden nest and heart unclenched at last may learn its rest. Redford found inspiration in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem, “Peace”: When will you ever, Peace, wild wood dove, shy wings shut, Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs? When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? And in a reverse nod to Dylan Thomas, h e prays that “my sister’s soul may indeed ‘go gentle into that good night’ after a death of such unimaginable violence.” “Rest Now, My Sister” is a solemn, courageous and loving tribute. As brother-in- law and composer, Redford offers Kristine — and others who hear his piece — an exquisite, genuine response to her death and to her life. Just as other composers and artists have turned to what they know best to assuage their feelings, J.A.C. has taken an act of destruction and answered it with an act of creation.

As the audience will see, this work also lends itself beautifully to interpretive dance, thus adding a new dimension to the creative circle of the Utah Chamber Artists.

11. “Feux follets” from 24 Pièces de fantaisie:

Deuxième Suite, Op. 53, Louis Vierne (1870-1937)

“Feux follet” (Will o’ the Wisp) has reference to the phosphorescent light caused by swamp gas as it appears to flit and dance about in the night air. In a more superstitious age this strange natural phenomenon was thought to be the apparition of malevolent spirits who would lead unwary travelers off the beaten path and into the treacherous swamps where death awaited. Vierne, among other composers, saw it as a way to evoke magical affects on his instrument.

12. Neue Liebeslieder, op. 65, Nos. 13 and 14

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

“What is this thing called love?” — Cole Porter’s 1929 classic could easily serve as a one-sentence summation of Brahms’ “Love-song Waltzes”. Set to poems by Georg Daumer, these delightful, ever-popular pieces are in fact sophisticated Ländler (the familiar German folk dances with their characteristic OOM-pah-pah beat) inspired by Brahms’ editing of 20 such pieces for piano by Franz Schubert. Daumer’s poetry (from his collection Polydora– also derived from folk traditions) covers the gamut of emotions from passionate rapture to longing and loneliness. But rather than forming a connected narrative, such as one finds in the typical Romantic song cycle, Brahms’ selections are individual miniatures, each with its own comment on the nature of love. Some are jolly and light-hearted, others ironic, introspective, or sad; often the sentiment is left to dangle incomplete or unexplained.

Brahms actually composed two sets of Liebeslieder: Op. 52, with 18 songs, and Op. 65, with Tonight’s performance presents two songs from Op. 65: No. 13, “Nein, Geliebter, setze dich,” is a soprano-alto duet, while No. 14, “Flammenauge, dunkles Haar,” begins with the same soprano-alto duet, followed by a second section for SATB voices.

In program notes for a performance by the Chicago Chorale, Bruce Tammen provides an amusing anecdote regarding Brahms’ fascination with Daumer and his folk verses:

Late in Daumer’s life, Brahms, who had never met the poet, or even corresponded with him, decided to pay him a visit. As he later wrote to his friend, poet Klaus Groth, “in a quiet room I met my poet. Ah, he was a little dried-up old man! . . . I soon perceived that he knew nothing either of me or of my compositions, or anything at all of music. And when I pointed to his ardent, passionate verses, he gesture, with a tender wave of his hand, to a little old mother almost more withered than himself, saying, ‘Ah, I have only loved the one, my wife!’”

13. Seguidilla from Carmen

13. Seguidilla from Carmen

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Bizet’s opera is the age-old story of fidelity versus temptation, and predictably, it doesn’t end well. Carmen, a lithe and sensuous gypsy girl, has been arrested for stabbing another girl at the cigarette factory where they work. Soldiers from the nearby garrison in Seville have brought her to their headquarters for arraignment and having tied her hands, left her in charge of a handsome corporal, Don José. Although his love has been promised to a lovely but naïve local girl, Micaela, Don José is immediately attracted to the hot-blooded Carmen, who sings tauntingly of love. Despite attempts to ignore her seductive advances, Don José is drawn inexorably to her charms. Tragedy ensues, but, of course, it makes for great opera, as Bizet fashions one knockout number after another, including this memorable Seguidilla (a seductive Spanish dance) that has become one of the most recognized arias in all of opera.

14. O Clap Your Hands

Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

A classic of 20th-century choral music, this anthem is an exuberant setting of selected verses from Psalm 47, composed for the Anglican service and meant to fill the church with exalted sound. The opening fanfare is a call to worship, immediately suggesting the Hebrew shofar (ram’s horn), calling the children of Israel to assemble for the word of God at Mt. Sinai. After the jubilant opening the music becomes suddenly introspective with a solemn, chant-like reading of the line, “For God is the King of all the earth: sing ye praises, everyone that hath understanding,” an expression of humility before the Almighty Presence, followed by a second eruption of joy, with a jubilant return of the opening pageantry: “God reigneth over the heathen: God sitteth upon the throne of his holiness.”

Truly, a “joyful noise” unto the Lord.